Introduction

Discuss this blog post on Maven, the world’s first serendipity network.

Much of my work gravitates around quantitative research of financial markets, for the most part working with custom-developed tools. When I started looking at risk management in the fast-moving crypto market, I wanted to try some new techniques based on the DeepCausality crate. Also, the recent SEC approval of Bitcoin ETFs made it clear that crypto is here to stay, and that’s just the perfect excuse to dive deep into quantitative research on crypto markets. All I needed was a backtesting facility to replay all trades from all markets and listen in to an exchange.

I built just that for 700 markets listed on the Kraken exchange, with nearly one billion rows of trade data. For the impatient engineer, feel free to go to check out the project on GitHub. The system is built with Fluvio as a message system and uses the DeepCausality crate for real-time analytics. Fluvio is built from the ground up for real-time event processing, thus is an obvious choice. DeepCausality is a blazingly fast computational causality library for Rust, capable of running tens of thousands of inferences per second on a laptop at microsecond latency.

I limited this project’s scope to building an end-to-end real-time data streaming system with a causal inference example mainly to showcase the whole picture without getting lost in any particular details. I believe any seasoned engineer can figure out the details when needed. Also, this system is not meant for 24/7 operation although it already contains a few sanity checks, observability, and error propagation. It is meant purely for educational purpose and to showcase what can be done already today with Rust, Fluvio, and DeepCausality with a sneak peak into the future at the end of this post.

Why?

Why this project?

Market data streaming systems come with some distinct requirements:

- Market replay is always message-based, so you use event-driven architecture.

- As a result of that, error handling is also event-based.

- The database must support fetch or pagination to stream queries continuously.

When you develop real-time systems that do risk assessments, measure volatility, or monitor VAR (Value at risk), you will probably explore many new ideas during the initial research. Next, you build these systems as closely to the actual market reality as you can. Therefore, you need a backtesting facility that replays the trade data as continuous streams, exactly as you would get them live from the exchange.

However, building an event-based backtesting facility takes meaningful time and effort, and is rarely available as open source. There are several Python-based crypto libraries out there for live data streaming, placing orders on exchanges, or building trading bots, but nothing resembling an event-based backtesting facility. Despite its popularity in the blockchain and FinTech sphere, the Rust crate ecosystem offers surprisingly few solutions meaning I did not found an event based backtesting engine written in Rust during my initial research. While Rust may not give you a ready-to-use solution, it certainly provides handy building blocks for building a production-ready system.

Therefore, it was time to roll up my sleeves and fill the gap. The catch is that the last time I worked on something similar, the entire system was written in Golang. That is to say, I started with zero experience with async message processing in Rust, let alone continuous async queries. Therefore, I started out this project mostly as a learning exercise to settle some questions I had about the Rust ecosystem. I wanted to know if there is a production ready message system written in Rust that can be used for this project, and if so, how well does it perform? Next, I was eager to learn how good Async works in practice. And the, it was largely unknown how well SBE message encoding would work with Rust given that Rust support was added only recently. Finally, I wanted to see how good Rust and cargo works in a mono-repo structure. A lot of questions had to be answered, and spoiler alert, I found answers to all of them and wrote the entire project in Rust.

Why Fluvio?

Embracing the unfamiliar, I adopted Tokio as an async runtime, but then hit the next roadblock; I needed a fast and reliable message bus that wasn’t Kafka. You see, I have zero objection to deploying Kafka in a multi-million-dollar enterprise that can digest the infrastructure bill that comes with it, but when it comes to my own wallet, I want the best value for money. Kafka doesn’t cut it. Next, I had an idea: Why not make it a 100% Rust project and find a new message system that interacts nicely with Tokio Async and doesn’t cost a fortune in terms of infrastructure?

In response to the new challenge, I’ve looked at various new message systems written in Rust. After seeing the good, the bad, and the ugly, I’d almost given up on messaging in Rust. Almost. On a last-ditch Google search, I found the Fluvio project that ticks all three boxes: It’s written in Rust, works with Async, and is cheaper- actually a lot cheaper- to operate than Kafka.

Conventionally, for data streaming analytics, an existing Kafka deployment would be used together with Apache Spark or Flink to add real-time data analytics. For Kafka, the legacy JVM drives up most of the cost because, for any performance level, Java application requires more hardware, which is simply more expensive. Specifically, Kafka requires ~1 GB of RAM per partition, whereas Fluvio only requires ~50 MB of RAM per partition.

When you use Rust and Fluvio, you accomplish real-time data streaming at a fraction of the operational cost. For example, one company migrated from Kafka to Fluvio and saw its annual cloud expenses drop by nearly half a million dollars annually.

Why DeepCausality?

For real-time analytics, one would conventionally write Scala programs for Apache Spark or Flink, but an equal step operational cost is implied. Some industry practitioners report that the expenses required to operate Spark exceed 50% of the project budget. In this case, the high cost isn’t so much driven by the JVM but rather by costly support contracts and, even more so, by expensive GPU hardware. A state-of-the-art A100 GPU can cost you $3800 per month, and at scale you need a lot of them, so your cloud bill balloons. Supposing you are already heavily invested in the Spark / Flink ecosystem, you could look closely at alternate GPU providers such as Lambda Labs, Oblivious, or TensorDock to lower your GPU bill.

On the other hand, if you’re not invested in the Kafka/Spark/Flink ecosystem, you can explore the innovative Rust ecosystem to look for alternatives. Contemporary Ai comes in two categories: One is DeepLearning that gets all the headlines with capabilities of driving LLMs like ChatGPT. The other one is Computational Causality, which is lesser known, but drives the success of streaming companies like Netflix. More specifically, Netflix has built its successful recommendation engine based on three themes: Time, Context, and Causality. While Netflix’ secret causality engine remains secret for the time being, computational causality has become available to the Rust ecosystem via the DeepCausality crate. DeepCauslity pioneers a new direction of computational causality and contributes three key novelties:

-

Context. You can add a context from which the causal model derives additional data. Since version 0.6, you can add multiple contexts. To my knowledge, that is the first causality library that provides built-in support for multiple contexts.

-

Uniform conceptualization of dimensionality. A uniform conceptualization of space, time, spacetime, and data, all uniform and adjustable, enables the bulk of contextual expressiveness.

-

Transparent composability. You can define causal relations as a singleton, multiple in a collection, or a hyper-graph. However, structurally, all three are encapsulated in a monoidic entity called Causaloid, which allows causal relations to be composed freely. In other words you can define causal relations as a collection of singeletons, store that collection in a graph, then put that entire graph as a node into another causal graph and then reason freely over single parts, selected sub-graphs or the entire graph. As a result, you can break down otherwise complex models into smaller parts and freely assemble them together. As we will see later, the composability extends even further to crates,

The DeepCausality context guide elaborates on all three topics in more detail.

With Rust, Fluvio, and DeepCausality selected, I was good to go. Next, let’s look at the project structure.

Project Structure

The project follows a handful of best practices for mono-repos with the idea of scaling up the code base quickly. One critical practice is the declaration of internal dependencies in the workspace Cargo. config file, as discussed in this blog post. Another essential practice is to move shared modules into a separate crate. As a result, the project comprises of a fairly large number of crates (> 20) relative to the small code size (~10K LoC). The underlying reason is that incremental compilation simply runs faster when modules are separated as crates. The most important crates of the project are:

- flv_cli/data_importer – A tool to import the Kraken data into the database.

- flv_clients

- QD Client that connects to the data gateway.

- SYMDB Client that connects to the symbol master DB.

- flv_common – Types and structs commonly used in all other crates.

- flv_components – Contains several components that provide a coherent functionality.

- flv_examples – Multiple code examples for streaming data.

- flv_proto – Proto buffer specification for the symbol master database service.

- flv_sbe – Simple Binary Encoding (SBE) specification, Rust bindings, and message types.

- flv_services – Contains the data gateway and the symbol master service.

- flv_specs – Contains various specifications and configurations.

In addition to these crates, there are a few more relevant folders:

- data – Empty. Put the Kraken data here to import. Feel free to read the data import guide for details.

- doc – Contains relevant project documentation written in Markdown.

- scripts – Bash scripts that are used by make. Read the install guide for details.

- sql – SQL statements for exploring the data set.

- tools – Contains the SBE tool that generates the Rust bindings. Note, the Rust bindings are already in the repo, so you don’t need to use this tool. The SBE tool is only in the repo because it’s a patched version that irons out a few kinks in the default distribution. It’s safe to ignore unless you want to develop with the SBE format.

With the project structure out of the way, let’s look at the architecture next.

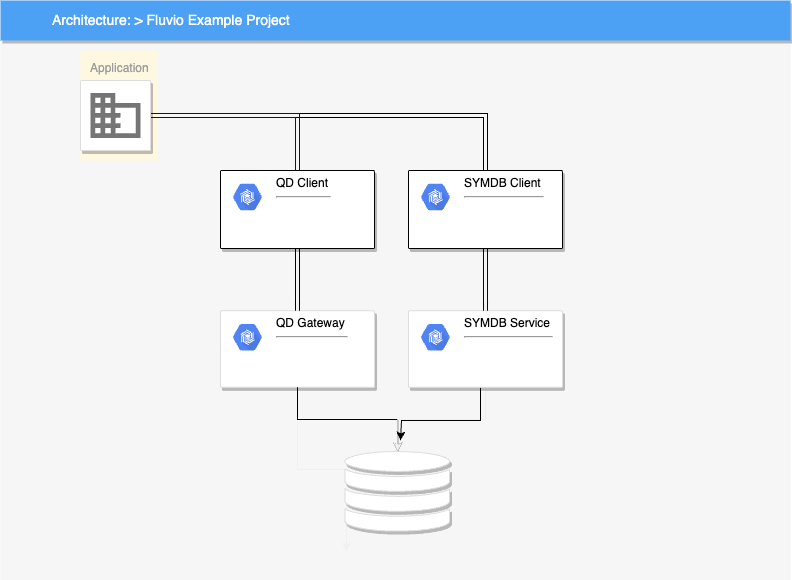

Architecture

The architecture follows the gateway pattern, meaning applications do not connect to the database directly. Instead, each application creates a QD Client that connects to the QD Gateway. The gateway handles essential tasks such as login/logout of clients. Likewise, the mapping from symbols to unique IDs happens via the Symbol Master Database (SYMDB) service. An application connects via the SYMDB client to the symbol service, resolves symbols it wants to stream data, and then connects to the QD gateway to request data streaming for the resolved symbols.

QD Communication Protocol

The communication between the QD client and gateway follows a simple protocol.

- The client sends a login message with its client ID to the gateway.

- A client error message gets returned if the client is already logged in.

- If the client is not yet known, the login process starts. Notice that the gateway only returns error messages but no login success messages which means it is the application’s responsibility to monitor the QD client for errors. If there is no error, it is safe to proceed.

-

Once connected, the client can send a request for either trade data or sampled OHLCV data at a resolution defined in the request message.

- The gateway returns an error if the requested data is unavailable.

- If the data is available, the gateway starts the data streaming.

-

When no further data is needed, the QD client is supposed to send a logout message to the gateway by calling the QD client’s close method. If this does not happen, the next login attempt with the same client ID will result in an error.

QD Gateway

The Quantitative Data Gateway (QDGW) is a gateway implemented as a Tokio microservice that streams financial market data from a database to connected clients. The QDGW exposes a Fluvio topic for clients to connect to. Clients can send requests and receive responses over this topic, and it handles client login/logout and maintains a state of connected clients.

The gateway processes clients’ requests for market data as trades or OHLCV bars by fetching the data from the database, serializing it into SBE messages, and streaming it to clients over their data channel. If there are issues processing a request, the gateway sends any error responses back over the control channel, and it maintains symbol metadata like symbol ID mappings, data types available, etc., to fulfill data requests correctly.

Service Configuration

The QDGW configures itself using the configuration manager based on the service specification defined in the service_spec crate. As you add more services to a system, managing service configuration becomes increasingly more complex, and configuration mistakes tend to occur more frequently.

In response, I have developed a simple auto-configuration system to ensure each service self-configures correctly using a configuration manager. The component reads the service specs from a crate and provides methods that give access to various configurations. In larger systems, service specifications would probably be stored in a database, which the configuration manager would read. Because each service is uniquely identified by an Enum ServiceID, the configuration manager ensures each one gets only the configuration specified for that service. With this system, it is easy to reconfigure the service by updating its specification in the service spec crate.

Client handling

The gateway handles client login messages by extracting the client ID and checking if the they are already logged in. If so, it returns an error. Otherwise, it logs the client in. During the login process, the gateway creates a data producer for the client’s data channel to which the data will be streamed. This allows the gateway service to securely stream data to channels that only the client can receive.

Data handling

The gateway similarly handles data request messages. It extracts the client ID, verifies that the client is logged in, and if so, looks up the channel name to which the data will be sent. In case of an error, a message will be sent to the client’s error channel. If there is no error, the gateway starts the streaming process.

Query vs. Fetch Data

Conventionally, one would query a database, collect the results in a collection, and then iterate through the collection and send out each row as a message. This may work for smaller setups to some degree, but some of the markets on Kraken have well over 50 million trades, so just the query alone would take some time. There is a risk of timeout and, certainly, excessive memory usage since the entire trade history would be loaded into memory before streaming to the client could start.

Instead, it is preferable to fetch data as an SQL stream and process each row as it becomes available and stream immediately to the client. In the background, the database probably uses pagination and batches of results until all rows have been returned. Regardless of the details, the QD gateway uses fetch mainly to prevent timeouts and excessive memory usage for larger datasets. Specifically, memory usage is at least tenfold lower for using fetch on the database.

However, the QueryManager used by the QD gateway implements both query and fetch, so depending on the use case, it can do either. By observation, query allows for more sophisticated SQL queries but isn’t great at loading large datasets, whereas fetch excels at bulk data streaming, but only if the query is relatively simple and fast to execute.

QD Client

The QD (Quantitative Data) client is used to connect to the QD Gateway (QDGW) service to request and consume market data streams. Upon initialization, the QD client uses the Fluvio admin API to create client-specific topics that only the client knows. One crucial detail is that in Fluvio, only the admin API can create or delete topics, whereas the regular API cannot. In a production environment, the admin API can be secured with authentication, but in this project, I’ve skipped the security setup for simplicity. You create an admin API simply by calling the constructor:

let admin = FluvioAdmin::connect().await.expect("Failed to connect to fluvio admin");

Once you have an admin API, you must construct a common request and a topic specification before sending the request to the cluster. You do that in two steps, as seen below.

async fn create_topic(admin: &FluvioAdmin, topic_name: &str) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Define a new topic

let name = topic_name.to_string();

let dry_run = false;

let common_request = CommonCreateRequest { name, dry_run, ..Default::default() };

// Ok, specify the topic config

let topic_specs = TopicSpec::new_computed(1, 1, None);

// Create the topic

admin

.create_with_config(common_request, topic_specs)

.await

.expect("Failed to create topic");

Ok(())

}

The delete API is a simple, you just pass in the name of the topic to the admin API.

async fn delete_topic(admin: &FluvioAdmin, topic_name: &str) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

admin

.delete::<TopicSpec>(topic_name.to_string())

.await

.expect("Failed to delete topic");

Ok(())

}

The full implementation of create and delete topic is available in the flv_utils file of the QD client. The QD client dynamically creates its topics upon initialization. Next, the QD client initializes a connection to the Fluvio cluster. It then sends a ClientLogin message to the QDGW to log in.

When the application calls a request data method, the QD client sends a data request message to the QDGW for either trades or OHLCV bars for a specific symbol. The QD client listens to its data channel topic for the responses from the gateway. The QDGW sends the requested data serialized as SBE messages. Error messages from the gateway are received over the client error channel. Sending a message in Fluvio is easy and follows the well-established producer/consumer pattern. For completeness, the send method of the QD client is shown below:

pub(crate) async fn send_message(&self, buffer: Vec<u8>) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Send the message.

self. producer

.send(RecordKey::NULL, buffer)

.await

.expect("[QDClient/send_message]: Failed to send Done!");

// Flush the producer to ensure the message is sent instantly.

self. producer

.flush()

.await

.expect("[QDClient/send_message]: Failed to flush to message bus.");

Ok(())

}

Flush is called immediately because the QD client only sends a single message at a time and therefore the producer can flush immediately. If you were to send bulk data, Fluvio has a number of settings to optimize message batch and send from the producer, and you wouldn’t have to flush explicitly until you have the last message to send. Please consult the Fluvio documentation for more details on optimization.

One more detail: Fluvio usually sends key/value pair messages so that you can use the key to identify the message type. However, because SBE-encoded messages already have the message type fully accessible, each message is sent without a key, thus saving a few bytes on the wire.

Upon shutdown, the QD client sends a ClientLogout message to the gateway to cleanly disconnect. It then deletes all

previously generated client topics. See

the close method in the QD client implementation for details.

All messages exchanged between the QD gateway and the QD client are fixed-sized

binary encoded SBE messages.

SBE Message Encoding

The Financial Information Exchange Standard (FIX) has glued the entire financial industry together for decades. Interestingly, until version 4.4, the FIX format was all text-based despite the well-known deficiencies of text processing in low latency systems. Simple Binary Encoding (SBE) is a modern FIX standard for binary message encoding and is optimized for low latency and deterministic performance. The official standard and full FIX schema can be downloaded from the FIX community.

It is well known that in message-based systems, throughput and latency depend on the message size, meaning a smaller message size usually results in lower latency and higher throughput. The average market on Kraken has well over a million recorded trades; therefore, message throughput matters. Performance benchmarks have shown that SBE delivers among the smallest message sizes and the fastest serialization/deserialization speed compared to other binary formats. The biggest difference, though, is between text-based JSON and SBE, in which SBE delivers a full order of magnitude more operations per microsecond.

For this project, a much smaller and simpler custom SBE schema was designed specifically for small message sizes. See GitHub for the schema definition file. In the custom SBE schema, the largest data message counts 40 bytes, and most control messages count less than 30 bytes in size, hence allowing for high throughput and low latency processing. Enums encoded as u8 integers were repeatedly used in the SBE schema to reduce message size. Furthermore, instead of using strings for ticker symbols, u16 integer IDs were used to reduce message size further. To map between ticker symbols and the numeric integer ID corresponding to a ticker, a symbol manager was added as a component, to easily look up IDs for symbols.

Another trick is to avoid SBE Enums and instead use u8 fields with Rust Enums cast into u8. The idea of SBE Enums is to limit and specify the number of valid values. The problem is that you do the same thing in Rust already, and then you would have to map back and forth between SBE and Rust Enums. Therefore, in a Rust-only environment, it is safe to declare the SBE field as u8 and encode the Rust Enum as a u8 in SBE, and decode the SBE u8 as a Rust Enum. However, please don’t do this in a multilingual project where multiple programming languages exchange data via SBE because the counterpart is not guaranteed to process your raw u8 value correctly.

Working with SBE is straightforward: you write an XML schema that describes your types and messages, run the SBE tool to generate the Rust bindings, and then define a proper Rust type with the added SBE encoding and decoding. The XML schema is necessary because SBE generates bindings for other programming languages, and XML was chosen as the lowest common denominator that works with every supported language and platform.

Symbol Master (SYMDB)

One challenge related to binary-encoded messages is how to map symbols to the corresponding numeric ID. During the data import, numeric IDs are assigned based on a first-come, first-served principle, so there is no particular order or system in place.

For this project, a basic symbol master service has been implemented that maps the Kraken symbols to the corresponding numeric ID. This allows application developers to just pull a symbol list either from the database or directly from the Kraken API, select a set of symbols, and then use the symbol master to translate these symbols to numeric IDs as required for the message encoding. When SBE binary encoded data arrives at the QD client, then the same symbol master service enables the reverse translation of the numeric ID back to the corresponding symbol. For the scope of this project, this solution is sufficient and serves as a starting point to add more advanced functionality.

There is a noticeable difference between regulated financial markets and crypto markets. In regulated financial markets, currency symbols and stock tickers have globally standardized unique IDs. In the still-young crypto industry, no standard exists with the implication that the same cryptocurrency is listed under different symbols on different exchanges. Because of this, a Zoo of half-baked solutions exists. One solution is to pick a commercial integration service provider, such as Kaiko or CoinAPI, and simply adopt their symbol mapping. This only works reliably if you subscribe to their paid data feed. Another solution is to use a public platform such as CoinMarketCap as a reference for symbol mapping. Usually, the public API allows you to download the symbol mapping, but that still leaves you with some integration work to map these back to actual exchange symbols.

When you want to support more than one exchange, you need a symbol master service to look up exchange-specific symbols. Note, the API signature of the symbol service requires an exchange ID; therefore, extending the symbol master service to support multiple exchanges is fundamentally possible but requires some engineering work to implement.

Real-Time Analytics

Once a data-stream has been established, you receive SBE encoded messages of either trade data or OHLCV bars. Trade bars usually reflect the spot price at which the last order was matched in the order book. While OHLCV bars have lower resolution, they often serve a purpose to establish points of reference. In quantitative research, these are called pivot points, reflecting the reality that at that price level, the market tends to pivot and basically make a U-turn. Pivot points remain instrumental in risk management because in markets, once the price is past a pivot point, at least you know the expected U-turn didn’t happen, so you have a starting point to make an informed guess. To make this kind of assessment, you need a model. Remember, there are three ingredients to a successful model:

- Time

- Context

- Causality

The Model

For this project, a fictitious monthly breakout model has been invented and implemented that showcase how to design real-time analytics that rely on temporal context to express causal relations. Please understand that the model is entirely made up and was never empirically validated, meaning there is no way you should use this model on your trading account if you don’t want to go broke. Also, the purpose of this post isn’t about financial modeling but rather about showcasing how to apply causal models to real-time data streams in Rust. With that out of the way, let’s look at the actual model:

use crate::prelude::{context_utils, CustomCausaloid, CustomContext, TimeIndexExt};

use deep_causality::errors::CausalityError;

use deep_causality::prelude::{Causaloid, NumericalValue};

use rust_decimal::Decimal;

/// Builds a custom [`Causaloid`] from a context graph.

///

/// Constructs a new [`Causaloid`] with the provided context graph,

/// causaloid, author, description, etc.

///

/// The built model contains the full context graph and causaloid

/// representing a causal model.

///

/// # Arguments

///

/// * `context` - Context graph to include in the model

///

/// # Returns

///

/// The built [`Causaloid`] .

///

pub fn build_causal_model<'l>(context: &'l CustomContext<'l>) -> CustomCausaloid<'l> {

let id = 42;

// The causal fucntion must be a function and not a closure because the function

// will be coercived into a function pointer later on, which is not possible with a closure.

let contextual_causal_fn = contextual_causal_function;

let description = "Causal Model: Checks for a potential monthly long breakout";

// Constructs and returns the Causaloid.

Causaloid::new_with_context(id, contextual_causal_fn, Some(context), description)

}

fn contextual_causal_function<'l>(

obs: NumericalValue,

ctx: &'l CustomContext<'l>,

) -> Result<bool, CausalityError> {

// Check if current_price data is available, if not, return an error.

if obs.is_nan() {

return Err(CausalityError(

"Month Causaloid: Observation/current_price is NULL/NAN".into(),

));

}

// Convert f64 to Decimal to avoid precision loss and make the code below more readable.

// Unwrap is safe because of the previous null check, we know that the current price is not null.

let current_price = Decimal::from_f64_retain(obs).unwrap();

// We use a dynamic index to determine the actual index of the previous or current month.

// Unwrap is safe here because the build_context function ensures that the current month is always initialized with a valid value.

let current_month_index = *ctx.get_current_month_index().unwrap();

let previous_month_index = *ctx.get_previous_month_index().unwrap();

// We use the dynamic index to extract the RangeData from the current and previous month.

let current_month_data = context_utils::extract_data_from_ctx(ctx, current_month_index)?;

let previous_month_data = context_utils::extract_data_from_ctx(ctx, previous_month_index)?;

// The logic below is obviously totally trivial, but it demonstrates that you can

// easily split an arbitrary complex causal function into multiple closures.

// With closures in place, the logic becomes straightforward, robust, and simple to understand.

// 1) Check if the previous month close is above the previous month open.

let check_previous_month_close_above_previous_open = || {

// Test if the previous month close is above the previous month open.

// This is indicative of a general uptrend and gives a subsequent breakout more credibility.

previous_month_data.close_above_open()

};

// 2) Check if the current price is above the previous months close price.

let check_current_price_above_previous_close = || {

// Test if the current price is above the previous months close price.

// gt = greater than > operator

current_price.gt(&previous_month_data.close())

};

// 3) Check if the current price is above the current month open price.

// This may seem redundant, but it safeguards against false positives.

let check_current_price_above_current_open = || {

// Test if the current price is above the current month open price.

current_price.gt(¤t_month_data.open())

};

// 4) Check if the current price exceeds the high level of the previous month.

let check_current_price_above_previous_high = || {

// Test if the current price is above the high price established in the previous month.

current_price.gt(&previous_month_data.high())

};

// All checks combined:

//

// 1) Check if the previous month close is above the previous month open.

// 2) Check if the current price is above the previous months close price.

// 3) Check if the current price is above the current month open price.

// 4) Check if the current price exceeds the high level of the previous month.

if check_previous_month_close_above_previous_open()

&& check_current_price_above_previous_close()

&& check_current_price_above_current_open()

&& check_current_price_above_previous_high()

{

// If all conditions are true, then a monthly breakout is detected and return true.

Ok(true)

} else {

// If any of the conditions are false, then no breakout is detected and return false.

Ok(false)

}

}

This model is as straightforward as it looks. To summarize its function:

- It defines the causal function that will check for the monthly breakout condition.

- The causal function takes the price observation and context as arguments.

- It uses the context to look up the current and previous month’s data nodes.

- The data is extracted from the node.

- The current price is compared to determine a potential monthly breakout. This takes four steps:

- Check if the previous month’s close is above its open.

- Check if the current price is above the previous month’s close price.

- Check if the current price exceeds the current month’s open price.

- Check if the current price exceeds the high level of the previous month.

- If all four conditions are true, then a monthly breakout is detected and returns true.

At this point, it becomes evident why only certain analytics problems can be converted to causal models, whereas others that rely on predictions cannot. However, you will be amazed how many of those problems showcased in the model exist in the world. For example, IoT sensors monitoring pressure sensors at an industry facility for anomalies can be modeled in a very similar way. Conventionally, none of these problems are particularly hard to solve unless you deal with dynamic context or, worse, multiple contexts. In that case, DeepCausality with its support for multiple contexts brings a lot to the table.

In the model code, I want to highlight the following five lines:

let current_month_index = *ctx.get_current_month_index().unwrap();

let previous_month_index = *ctx.get_previous_month_index().unwrap();

// We use the dynamic index to extract the RangeData from the current and previous month.

let current_month_data = context_utils::extract_data_from_ctx(ctx, current_month_index)?;

let previous_month_data = context_utils::extract_data_from_ctx(ctx, previous_month_index)?;

When you look at the DeepCausality context API specification, it doesn’t contain the methods that get the current or previous month’s index. Instead, a type extension defines these custom methods. In this particular case, the TimeIndexExt is written as a type extension with a default implementation against the signature of a super trait implemented in the target type context. As a result, with a single import, you add new functionality to an external type. The formidable iterator_ext crate uses a similar technique to add more functionality to the standard iterator in Rust.

With the TimeIndexExt extension in place, the model above works out of the box even though the DeepCausality crate only provides the building blocks. For convenience, the entire model, with its context builder, protocol, type extension, and actual causal model definition, has been put in a dedicated crate.

That’s another particularity of DeepCausality models: they compose with standard tools such as Cargo so you can build large causal models from various building blocks in separate crates. Because of type extensibility, you may customize any aspect as needed as long as it links back to super traits implemented in the DeepCausality crate. If something is missing, feel free to open an issue or submit a pull request.

The Context

The context is a central piece of the model. It is the place where all related data are stored for the model.

In DeepCausality, a context can be static or dynamic, depending on the situation. The context structure is defined beforehand for a static context, whereas for a dynamic context, the structure is generated dynamically at runtime. Regardless of the specific structure, DeepCausality uses a hypergraph to internally represent arbitrary complex context structures.

The hypergraph representation of context in DeepCausality conceptualizes time as a non-linear category of unknown structure with the requirement that it is also linearly expressible to adhere to the common interpretation of time linearity under the time arrow assumption. That way, both linear and non-linear time scenarios can be represented.

Context provides either internal, external, or both types of variables to the causal model. Furthermore, whether variables are independent or dependent doesn’t matter because any dependent variable can be updated through change propagation via the adjustable protocol. In practice, that means you can derive context data from the data stream itself, from external sources, say Twitter sentiment, or any combination of internal and external data. By convention, for dynamic contexts, you update the context first before applying the model.

For this project, a static context is generated that adds range data for the year and month of the incoming data. This is a significant simplification compared to the actual reality but necessary to reduce complexity. As stated in the introduction, geometric causality reduces arithmetic complexity by increasing structural complexity. Since there is nothing difficult about the model, the complexity must be elsewhere. And indeed, the structural complexity has been shifted into the context.

Generating a context comes down to three steps:

- Load some data

- Transform data as necessary

- Build a context structure as required

All three steps are highly depending on the project requirements. However, for this project, I chose to build a static temporal graph augmented with range data. You find the full code of the context generator is in the project repo. The context graph is built by adding nodes for each month and year to the graph. By convention, a context graph starts with a root node, that is added as shown below.

// == ADD ROOT ==//

let id = counter.increment_and_get();

let root = Root::new(id);

let root_node = Contextoid::new(id, ContextoidType::Root(root));

let root_index = g.add_node(root_node);

The root node is a special node that has no parents and serves a structural point of reverse when dynamically traversing large graphs. The root node links to each year represented as temporal node. The temporal nodes are added as shown below.

// == ADD YEAR ==//

let time_scale = TimeScale::Year;

let elements = data.year_bars();

for data_bar in elements {

// Get year from bar

let year = data_bar.date_time().year();

// Augment OHLCV bar with time and data nodes

let (tempoid, dataoid) = context_utils::convert_ohlcv_bar_to_augmented(data_bar, time_scale);

// Create year time node

let key = counter.increment_and_get();

let time_node = Contextoid::new(key, ContextoidType::Tempoid(tempoid));

let year_time_index = g.add_node(time_node);

// Create year data node

let data_id = counter.increment_and_get();

let data_node = Contextoid::new(data_id, ContextoidType::Datoid(dataoid));

let year_data_index = g.add_node(data_node);

// .. Indexing

// println!("{FN_NAME}: Linking root to year.");

g.add_edge(root_index, year_time_index, RelationKind::Temporal)

.expect("Failed to add edge between root and year.");

// println!("{FN_NAME}: Linking year to data.");

g.add_edge(year_data_index, year_time_index, RelationKind::Datial)

.expect("Failed to add edge between year and data");

The month nodes are added in a similar fashion. When designing a context, you should think about the data that you want and the context structure that you want to build. It’s best to draw the desired structure on a sheet of paper before implementing it. Lastly, by experience, you are going to spent more time on building and debugging context than building the model itself. Please pay meticulous attention to correct indexing of the context graph as this is what makes the the causal model work.

Applied Contextual Causal Inference

In terms of applying the model to incoming data messages, it’s as simple as writing a standard event handler. The only meaningful difference is the particularity of SBE encoding. Because SBE is fixed-sized encoding, the position of the message ID in the byte array is always known upfront; therefore, you can extract the message ID without decoding the actual message. This is true for all primitive types in SBE, but for message ID it’s so convenient that it’s worth showing in action. From the XML schema, we know that message ID is always in the third position; here is how you extract and use the message ID for incoming data bars:

pub fn handle_message_inference(&self, message: Vec<u8>) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error + Send>> {

// The third byte of the buffer is always the message type.

let message_type = MessageType::from(message[2] as u16);

match message_type {

// Handle first trade bar

MessageType::FirstTradeBar => {

println!("{FN_NAME}: FirstTradeBar (Data stream Starts)");

}

MessageType::TradeBar => {

let trade_bar = SbeTradeBar::decode(message.as_slice()).unwrap();

// println!("{FN_NAME}: TradeBar: {:?}", trade_bar);

// println!("{FN_NAME}: Extract the price from the trade bar: {}", trade_bar.price().to_f64().unwrap());

let price = trade_bar.price().to_f64().unwrap();

println!("{FN_NAME}: Apply the causal model to the price for causal inference");

let res = self.model.verify_single_cause(&price).unwrap_or_else(|e| {

println!("{FN_NAME}: {}", e);

false

});

// Print the result of the inference in case it detected a price breakout

if res {

println!("DeepCausality: Detected Price Breakout!");

}

}

// Handle last trade bar

MessageType::LastTradeBar => {

println!("{FN_NAME}: LastTradeBar (Data stream stops)");

}

// Ignore all other message types

_ => {}

}

Ok(())

}

}

This is it. Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication. You extract an integer, convert it to an Enum that tells you what kind of message to decode, then you pattern match over that Enum. When you get a TradeBar, you decode it, extract the current price, convert it (from Decimal) to f64, and pass it to the model.

Everything here is standard Rust, including error handling, pattern matching, processing, and everything you find in the Rust book. By my internal measurements, the causal inference adds, at most, a single-digit microsecond latency to the message processing. You will never notice it if your real-time system operates at a millisecond level. Even if your system operates at a microsecond level, adding single-digit microseconds might be acceptable. When it’s not, you can still optimize the context with some clever lookup tables and probably get it faster.

What was left out?

Looking through the repo, you will unavoidably find things not mentioned in this post, simply because explaining the

entire code base in a single blog post post is infeasible. However, I have good news for you because this project is

exceptionally well-documented (just run make doc) and has plenty of unit tests. Browsing the code with the

documentation and tests

should help you understand whatever wasn’t mentioned in this post.

I have deliberately skipped a general introduction to Rust because it’s not the focus of this post. It is assumed when you read about real-time causal inference in Rust that you already have some experience writing software in Rust. At this point, the internet provides an abundance of material to learn Rust; just use your favorite search engine to find the best Rust resources for you.

I’ve omitted a general introduction to computational causality, mainly to keep the post readable. The DeepCausality project has documentation that covers the basics and more. For a gentle introduction to the field, read “The Book of Why?” by Judea Pearl, the grandfather of computational causality.

Lastly, I have left out a general introduction to quantitative finance and market modeling to keep the post to a reasonable length. There are several good books for any topic in quantitative finance. My top three go-to recommendations are Financial Modeling by Simon Benninga, Advances in Financial Machine Learning by Marcos López, and The Successful Trader’s Guide to Money Management by Andre Unger.

Future of Real-Time Data Processing in Fluvio

One particularity you may encounter in real-time systems is the prevalence of the microservice pattern. While the project’s code examples all show client-side processing, you could equally put a causal model or any other form of processing into a microservice. At least, that is a common conception unless you already have a full Spark cluster deployment. The Fluvio project already supports smart modules that allow you to perform common stream processing tasks such as collecting, transforming, deduplicating, or dispatching messages within the Fluvio cluster. However, the second generation of stateful services takes that concept one step further and allows for composable event-driven data pipelines using web assembly modules. Access to stateful services is currently in private preview, and I had chance to test it out. The technology is outstanding, and with those web assembly modules, you can replace a bunch of microservices. While the stateful service may take some time to mature, I am confident it will be on a similar quality level to the existing system. I recommend Fluvio as a message bus to cut the cloud bill and see how the stateful service evolves to see if your requirements can be met by the new paradigm. Like causal models, it won’t work for everything. Still, when it works, you will discover something truly intriguing that gives you capabilities previously thought unattainable. And you get it at an absurdly low operational cost.

Future of DeepCausality

Even though this project only scratched the surface of what DeepCausality can do, a few more features are planned. For once, a ticket is open to remove lifelines from the public API. When completed, the DeepCausality crate will work significantly better with concurrency code. Right now, these lifelines conflict with Tokio’s requirement that each task must own all its data to ensure thread safety. As a result, you cannot easily share a context between tasks via the usual Arc/Mutex wrapper, and therefore, async & concurrent context updates are currently too cumbersome. The lifeline removal is only a refactoring task and should be done sooner rather than later.

Modeling modular contextual causal propagation is an area that needs further exploration. Specifically, this means writing intermediate effects to the context of another downstream causal model, which then uses the updated context to reason further and writes its inferences into another downstream context. By implication, modular models result in modular reasoning, and at each stage, intermediate results remain encapsulated yet accessible to other models or monitoring systems. This approach is potent given that any of those models may have multiple contexts to feed into the causal model at each stage. The future of DeepCausality is evolving towards increasingly more advanced and sophisticated real-time causal inference.

Reflection

When I started with the project, several unknowns had to be answered. For once, it wasn’t clear if there was a production-ready messaging system written in Rust. That has been fully answered because Fluvio is certainly production-ready when it comes to messaging and even its initial version of Smart Modules works. During development I didn’t encounter any difficulties, and those few questions I had were quickly answered either from the documentation, the project Discord, or simply by looking into the source code.

Another unknown that had to be considered was the quality of Rust Async at the moment, given its rapid evolution over the past few years. Using it confidently is a no-brainer because the Tokio ecosystem works out of the box, and for every possible situation that may come up, there is either documentation or some online question that has already been answered. On that topic, Prost is perhaps the fastest and easiest way to write gRPC services and it beats the GoLang ecosystem by a mile. It might not be the fastest implementation regarding total requests per second, but once you have your proto file, you have a functional gRPC server within 30 minutes, depending on how fast you can type. It’s really impressive and an excellent example of how much better the development experience can be in Rust.

In addition, it wasn’t known how well SBE would work in tandem with Rust. Again, it was of no concern and they coordinated seamlessly. I just got things done. Fixed-sized binary formats are always a bit more verbose to work with, but the net gain in message throughput and latency you get due to smaller message sizes is well worth the effort.

Lastly, there is Cargo on a mono-repo. Historically, I’ve adopted Bazel early on whenever it was clear from day one that the code base would grow very fast and multiple 10x increases could be expected. There is a strong argument for Bazel, and probably plenty against too, but once your project is past the first 50k LoC, the choices of build systems that can cope with rapidly growing code are limited. Alternatively, Cargo gives you much more breathing space before a hard decision has to be made. Specifically, building 20 Crates with Cargo is a breeze, and works way better than expected. I estimate that you may be able to kick the can further down the road by another 10X, so only when you hit a 100K LoC or about 200 crates do you have to think hard about Bazel, mainly to get your release build time down. That’s reassuring and refreshing compared to what I have experienced with other ecosystems. By the time you hit 500K LoC, you end up with Bazel anyway.

Next Steps

Even though this project concluded, there would be a few steps more steps required to expand the QDGW into a fully-fledged quantitative data research system. First, the QD client needs some polishing so that it’s easier to use. As you can see in the code examples, programming the QD client with async processing isn’t as good as it could be.

Them adding more advanced features like the ability to backtest risk assessment or trading strategies would be another next step. There are two ways to backtest risk assessment or trading strategies. One way is to track positions on the clients’ side, which is usually more straightforward to implement. This is great for getting started, especially for single-instrument strategies. However, it isn’t very realistic as it does not consider trading fees, slippage, and order splitting. None of these matter for smaller positions because small orders rarely get split, and slippage usually doesn’t amount to much compared to trading fees. The second way is to implement a virtual exchange that emulates the execution and fee schedule of a particular exchange. If the virtual exchange solely relies on trade data, it cannot consider slippage and order splitting so there is diminishing return. If it is implemented using order book replay, then it can emulate slippage and order splitting. Be aware that order book reconstruction requires some sophisticated engineering and full quote data.

Lastly, a user interface for visualizing backtesting results would complete this project. UI in Rust remains one of the few areas where the ecosystem is still in its early days. There are a few great projects out there, such as Tauri, but I haven’t used it myself therefore I can’t comment on it.

About

Fluvio is an open-source data streaming platform with in-line computation capabilities. Apply your custom programs to aggregate, correlate, and transform data records in real time as they move over the network. Read more on the Fluvio website.

DeepCausality is a hyper-geometric computational causality library that enables fast and deterministic context-aware causal reasoning in Rust. Learn more about DeepCausality on GitHub and join the DeepCausality-Announce Mailing List.

The LF AI & Data Foundation supports an open artificial intelligence (AI) and data community, and drive open source innovation in the AI and data domains by enabling collaboration and the creation of new opportunities for all the members of the community. For more information, please visit lfaidata.foundation.